Whenever someone mentions a book to me, I always check it out, regardless of who’s suggesting it. Most of the time, I don’t end up reading it, but still, I don’t mind take a few moments to check out a book and see if it might interest me in the future. This makes me have a big library of books, both physical in digital, that I have no idea who suggested to me.

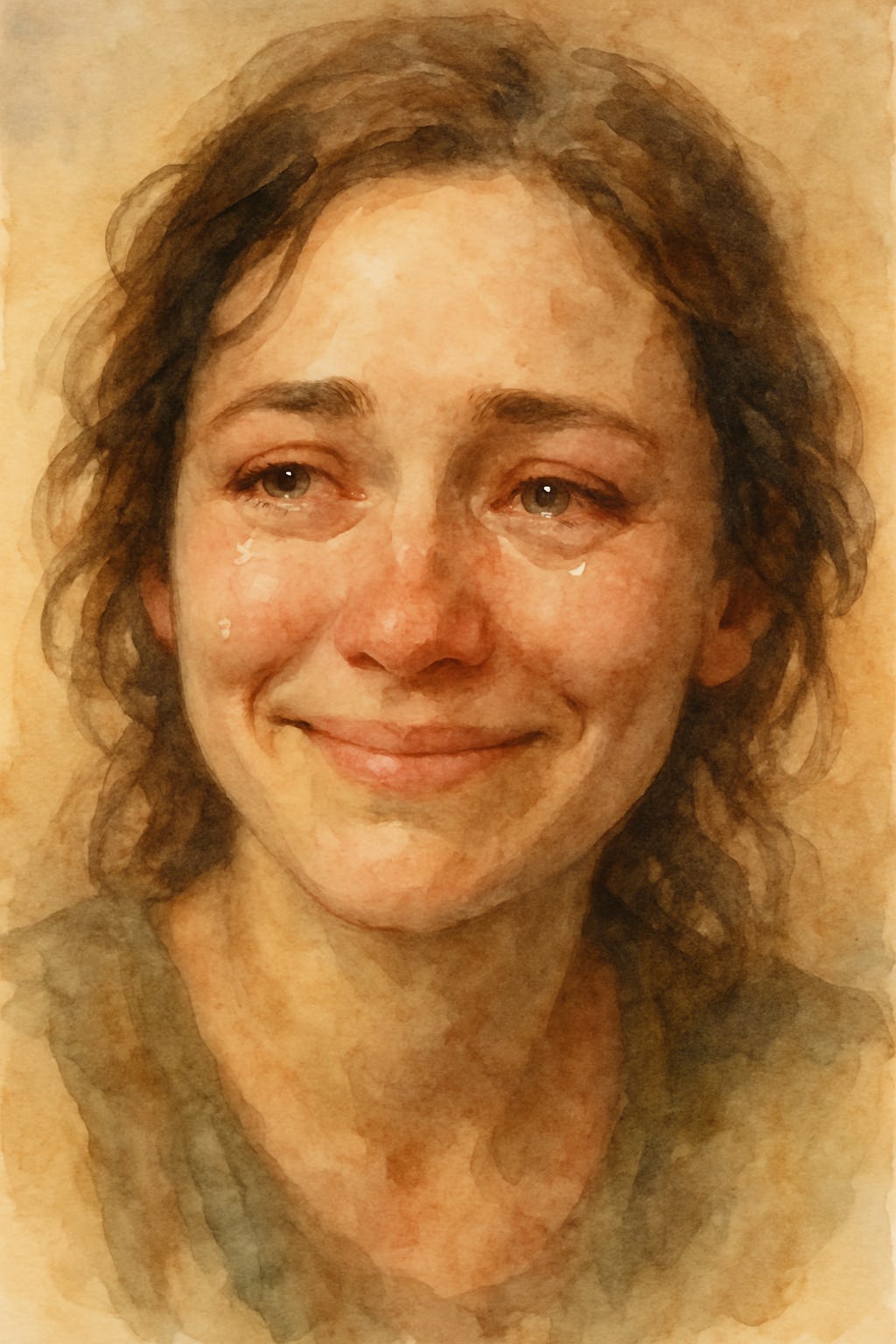

“Tuesdays with Morie” is one of those books. After going through “Amoralman”, which I mentioned in my previous essay, I was scrolling through my library in Apple Books and stumbled upon it. I read it for a couple of minutes and find myself doing “the crying chuckle”.

You might be wondering what I mean by that, so let me explain. It’s a personal habit of mine: when I get emotional and feel like I might cry, I tend to let out a small chuckle to hold back the tears. It usually happens just once—right when my throat tightens and my eyes start to well up. I realize this can be a bit jarring for others (especially my girlfriend, who has to hear me chuckle during the emotional parts of movies—sorry, love), but for me, it’s as instinctive as breathing. So when that familiar chuckle escaped in the first few pages of the book, I knew I was in for something special.

The book was written by Mitch Albom, a journalist and former student of Morrie Schwartz, who serves as the central figure of the story. Morrie was a beloved sociology professor at Brandeis University, widely respected for his compassion and quiet wisdom. After touching the lives of countless students, he was diagnosed with ALS, a progressive neurodegenerative disease that gradually shut down his nervous system.

Years after graduating, Mitch reconnected with Morrie and began visiting him regularly. Their conversations became the foundation for the book—what Mitch would later call “the final assignment” of their time together.

Here are the first paragraphs of the book:

The last class of my old professor's life took place once a week in his house, by a window in the study where he could watch a small hibiscus plant shed its pink leaves. The class met on Tuesdays. It began after breakfast. The subject was The Meaning of Life. It was taught from experience.

No grades were given, but there were oral exams each week. You were expected to respond to questions, and you were expected to pose questions of your own. You were also required to perform physical tasks now and then, such as lifting the professor's head to a comfortable spot on the pillow or placing his glasses on the bridge of his nose. Kissing him good-bye earned you extra credit.

No books were required, yet many topics were covered, including love, work, community, family, aging, forgiveness, and, finally, death. The last lecture was brief, only a few words.

A funeral was held in lieu of graduation.

Although no final exam was given, you were expected to produce one long paper on what was learned. That paper is presented here.

The book is really good, filled with small nuggets of that “gentle wisdom” I mentioned before. However, it wasn’t the “personal development” aspect of the book that really impacted me. It was the overall depiction of Death.

Mitch does a remarkable job of capturing the subtle details that reflect what it’s like to be around someone nearing the end of life. Small things—the lingering scent Morrie carried even after a shower, the roughness of his one-day beard that stung anyone who kissed him, the spots on his skin, and the quiet joy he felt from simple human touch—are all intimate moments familiar to anyone who has spent time with the elderly as they prepare to say goodbye to this world.

Even though Morrie was suffering, he had a clear mind, and continued to be as articulate as ever, until he wasn’t able to anymore. He gave a series of interviews on national television, bringing him widespread attention and a devoted group of admirers. They wrote to him with questions and reflections. Morrie always answered, borrowing from the hands of someone else, when he no longer was able to write. Some people went as far as calling him a prophet.

While the book offers plenty of wise advice about how to live, what drew me in most was its deeper, ongoing conversation about death and my own relationship with it.

Other than a friend who died in a motorbike accident when I was a teenager, I haven’t had many personal encounters with Death. One of my grandparents passed away when I was too young to remember, and the rest are still alive. Still, I’ve spent many hours volunteering in nursing homes, and I vividly remember the quiet weight of arriving to find an empty chair in the common room—a silent reminder to everyone, young and old, that sooner or later, people go away.

Of course, going through the book, I couldn’t help but think about all of this. I had witness all of those small details when playing guitar to these old souls in my volunteering days.

As I pondered about death, I thought of two people: Sr. Luís, my girlfriend’s grandad, who passed away last year, and my own grandmother, who earlier this week didn’t recognize her daughter, my mom.

Dealing with death is one of those elements in life that transcends a unique approach. During the last few months, I got into a series of conversations about it (maybe unconsciously influencing my own choice of reading this book), trying to understand if my own approach to it was “the right one”.

You see, I stopped paying visits to my grandma. And even though I feel like this is the right course of action for me, there’s always a lingering question, after all, contrary to most things, Death is irreversible, which means our approach to it, gets recorded into space and time.

I remember her fondly.

I remember her rice with carrots and sausages—and how much I loved that, unlike anyone else I knew, she’d cut the sausages lengthwise instead of into slices. I remember the variety of cakes she made, each with its own unique flavor. To this day, the only spinach cake I’ve ever tasted came from her. I remember her stories, always featuring an old grandma who ended up saving the day—and the night all of us cousins acted them out for her. I remember walking into her living room and finding her playing Mahjong on the computer, or playing “Zangados” (“Angry People”), where she’d chase me around the house. I remember going out to her little backyard and throwing old oranges as far as we could, trying to see who could throw the furthest.

I also remember the slow, steady decline. How she could no longer live on her own, moving from one son’s house to another, until she eventually settled in a nursing home. I remember how it took her longer and longer to recognize me. For a while, after a few questions, something would click—she’d realize who I was and smile. But eventually, we reached a point where no matter what we said or how much we tried, I became just another stranger standing in front of her.

The first time I learned about recency bias, I wasn’t aware of how much it would influence the way I would deal with this particular situation. It states that we have a higher tendency to remember the most recent things that we’ve learned or that have happened. The more I interacted with my grandma while she was decaying, the harder it got for the first set of memories to be the more present ones. This is what I told the people that I’ve spoken about this issue, and a friend, who went through something similar, admitted that he did the same. I feel his pain. It’s a choice to consciously do the thing that allows you to retain as many good memories as possible. It is, nevertheless, a painful choice.

I contrast this with the reality of my girlfriend’s late grandad, Sr. Luís.

I had the chance to closely witness how his family responded to his rapid, steady decline. Each family member, in their own way, worked tirelessly to adjust to his diminishing abilities—making constant efforts to support him and maintain his well-being. Even as hope for recovery remained alive—as it always does—their main focus was simply being there, offering presence and care.

In the book, Morrie often emphasizes that family is the one true pillar during times like these. No matter how close your friends may be, they won’t be there around the clock—massaging your blistered feet or helping you bathe.

Witnessing it was, indeed, profoundly beautiful. It doesn’t change my own approach to my grandma. After all, as I’ve said, Death is one of those things that challenges the idea of a single right approach.

At the end of the day, your beliefs deeply influence the way you process and act in such situations. To me, it’s easy to imagine Sr.Luís in a better place, a glass of scotch in his hand, looking down and smiling. In fact, I try to apply this thinking to everyone I know who might leave.

The book that I’ve reread the most in my life is Herman Hesse’s Siddartha. Here’s a passage that really shaped my own view around this:

Siddhartha listened. He was now nothing but a listener, completely concentrated on listening, completely empty, he felt, that he had now finished learning to listen. Often before, he had heard all this, these many voices in the river, today it sounded new. Already, he could no longer tell the many voices apart, not the happy ones from the weeping ones, not the ones of children from those of men, they all belonged together, the lamentation of yearning and the laughter of the knowledgeable one, the scream of rage and the moaning of the dying ones, everything was one, everything was intertwined and connected, entangled a thousand times. And everything together, all voices, all goals, all yearning, all suffering, all pleasure, all that was good and evil, all of this together was the world. All of it together was the flow of events, was the music of life. And when Siddhartha was listening attentively to this river, this song of a thousand voices, when he neither listened to the suffering nor the laughter, when he did not tie his soul to any particular voice and submerged his self into it, but when he heard them all, perceived the whole, the oneness, then the great song of the thousand voices consisted of a single word, which was Om: the perfection.

All of us are single voices, in a chorus made of all humans, connected through a common harmony.

Nevertheless, I think there’s value in letting your relationship with death influence the way you perceive the world. There is, indeed, a shift of perception.

“Mitch. Can I tell you something?" Of course, I said.

"You might not like it." Why not?

"Well, the truth is, if you really listen to that bird on your shoulder, if you accept that you can die at any time then you might not be as ambitious as you are."

I forced a small grin.

"The things you spend so much time on-all this work you do-might not seem as important. You might have to make room for some more spiritual things."

This is probably the one point where I strongly disagree with Morrie. It reminds me of conversations I’ve had with long-time meditators who say they’ve reached a place where they no longer want to do anything at all.

I believe that as you come to terms with death—as you develop a deep sense of acceptance and peace with the idea that “everything is okay”—you can still hold that mindset while actively building something meaningful. Inner peace doesn’t have to mean detachment from action. In fact, I think true acceptance should empower us to create things that uplift others, living a life of service.

Don’t get me wrong—if the meaning of your life is tied up in a soulless corporate job, working to maximize value for shareholders you’ll never meet, then by all means, meditate on your impermanence and explore the depths within you.

But if you’ve already reached a point of genuine acceptance—if you’ve come to peace with things as they are—that shouldn’t mean withdrawing from the world. On the contrary, that clarity should fuel your ability to shape the world into what it could be, using your gifts to help others live fuller, better lives.

Maybe, after your own journey of growth, you uncover a sacred ambition—or at least a quiet, steady will to serve something beyond yourself.

The reason I care so deeply about this idea of helping others comes from the most profound moment I experienced while Sr. Luís was dying.

One day, after he was hospitalized, my girlfriend and I went to her grandmother’s house—to offer support and keep her company while we waited for news. At some point, we received a phone call, which her grandma quickly put on speaker. On the other end, we heard my girlfriend’s mother reassuring us that everything was okay and asking if her grandmother wanted to speak with her husband. Without hesitation, she said yes. The moment she heard his voice, she asked how he was doing.

Now, this man was in the hospital. He had every reason to use that moment to focus on himself. But instead, his first words were: “How are you?”

That act of selfless love—of thinking about someone else even in the final stretch of his life—struck me deeply. It made me realize that our personal growth should lead us to a place where what matters most is not ourselves, but those around us.

Since then, I’ve come to believe that the ultimate goal isn’t reaching a stable state of inner contentment—it’s taking action to improve the lives of others.

Confronting my own mortality through the lives of others, made me realize that fulfillment lies not just in inner peace, but in using it as a bridge that others can cross in order to live a better life.