Introduction

Since my early days as a guitar teacher, I’ve been teaching classes in a one-on-one setting. To this day, it remains one of my favorite pedagogical features in music learning. When you have weekly classes directly with a single teacher, your learning curve grows exponentially, and you approach the “apprenticeship method” that shaped learning throughout most of human history. This is much closer to mentorship than to a traditional class since each student receives a tailored experience.

As a music teacher, I adapted my teaching style to whoever was in front of me, just as my own teachers did. I understood the deep value of this “mentorship” dynamic: to see how ideas take root and resonate uniquely in each student’s life, gathering more context on their worldview and environment.

Even though this happened early in my educational career, I’ve made an effort to maintain this approach. Specifically, for the past 5 years, I’ve been mentoring high schoolers at multiple levels, from coaching sessions regarding their learning to helping them set up businesses.

In What Drives Youth, I met regularly with members of our community and helped them with skill development. The entire pedagogical model I later designed for Entrepreneurial Gym has mentorship as the cornerstone. For the past 3 years, at The Socratic Experience, I’ve been fortunate enough to have several students as mentees.

Recently, I realized I had hundreds of notes on sessions with all of these students. Lessons, failed approaches, scattered thoughts…So, I compiled them all into an LLM and asked questions, searching for patterns in the data. I’ve had students from multiple countries, income levels, and many different interests, and yet, patterns emerged. The most meaningful one relates to the skills students developed through my mentorship meetings.

My approach to mentorship meetings

Besides the thousands of hours in music (both as a student and teacher), my courses on Pedagogical Competencies, Coaching, and Neurolinguistic Programming had a big impact on the way I think of one-on-one conversations. They’re the foundation of my mentorship structure across all projects.

They all start with the same question:

How do you want to grow?

Similar to a coaching process, we start by identifying what’s the starting point for each student, where they want to end up, and what resources they need to get there. Each of my mentees has a goal or project that they want to work on and an idea on what they must develop to achieve it. Since multiple people have multiple interests, there’s a lot of freedom for mentees to pick what they want to do. More than 90% of the time, sessions end up being about developing certain key skills that they need to develop.

Even if I’m not qualified to teach every skill that students need to learn, I can still guide them in developing the meta-skills and learning strategies that support their growth in any area they choose.

Meta skills are skills that are valid across multiple contexts. They’re interchangeable, applicable to multiple areas. By improving a certain skill in one area, it automatically makes you better at it in a different one. By elevating your writing, you’ll be able to connect deeper with people, convince others to invest in your business idea, or make someone angry. If you learn how to improve in music, you’ll be able to improvise better while playing charades, having a tough conversation, or having to brainstorming something.

Same skill, multiple contexts.

What I found fascinating is that, by looking at the dozens of mentees I’ve had over these last few years, it’s hard to see patterns other than age. It turns out I was wrong. Deeply wrong. Even though they have different backgrounds, projects, cultures, and countries, more than 80% of them wanted to develop 1 or more of the same set of 5 skills.

For the last 5 years, I’ve been mainly focusing on the same skill list:

Ownership;

Emotional Intelligence

Self-Confidence

Task management

Netwroking

I want to walk you through some basic notions on how I help students develop each one of them.

Ownership

I have a high tendency to have ownership as one of the first skills that I encourage students to develop. Understanding that they are responsible for much more than they usually give themselves credit for is one of the best ways to foster their sense of agency and make them comprehend their capacity to shape what surrounds them.

Teenagers tend to look for culprits in the world, framing themselves as victims of their environment, making them miserable. This dangerous combination, if left untouched, tends to breed resentful adults who lack any sense of responsibility, firmly believing that everything bad is somebody else’s fault.

If you ask a few thoughtful questions and listen carefully, you’ll soon uncover how they perceive their own limitations. Often, they’re expressed through the external factors they believe are holding them back. As a mentor, I want them to understand what they can control/influence and what’s just outside of that scope.

The weight of ownership is hard to bear, at least initially. Most of my mentees, like many adults, were highly resistant at first. It’s more comfortable to keep finding reasons to justify why something isn’t their responsibility. The key to helping them dissolve this initial resistance is to slowly build their understanding of how much they can actually handle, leading them to admit how much of their life is actually under their control or direct influence. It’s scary! But not scarier than a lack of freedom, something every teenager instinctively fights against.

Most times, I start by validating the student instead of trying to shift their vision from the get-go. Usually, as we talk, students end up putting themselves in a position of 100% passivity. They’re nothing but a little frightened animal, trapped by the outside world. However, once you frame it this way, pointing out that they’re giving away their freedom, there’s something that wakes within them. They develop a better sense of awareness around the narrative that they’re building about themselves and the world.

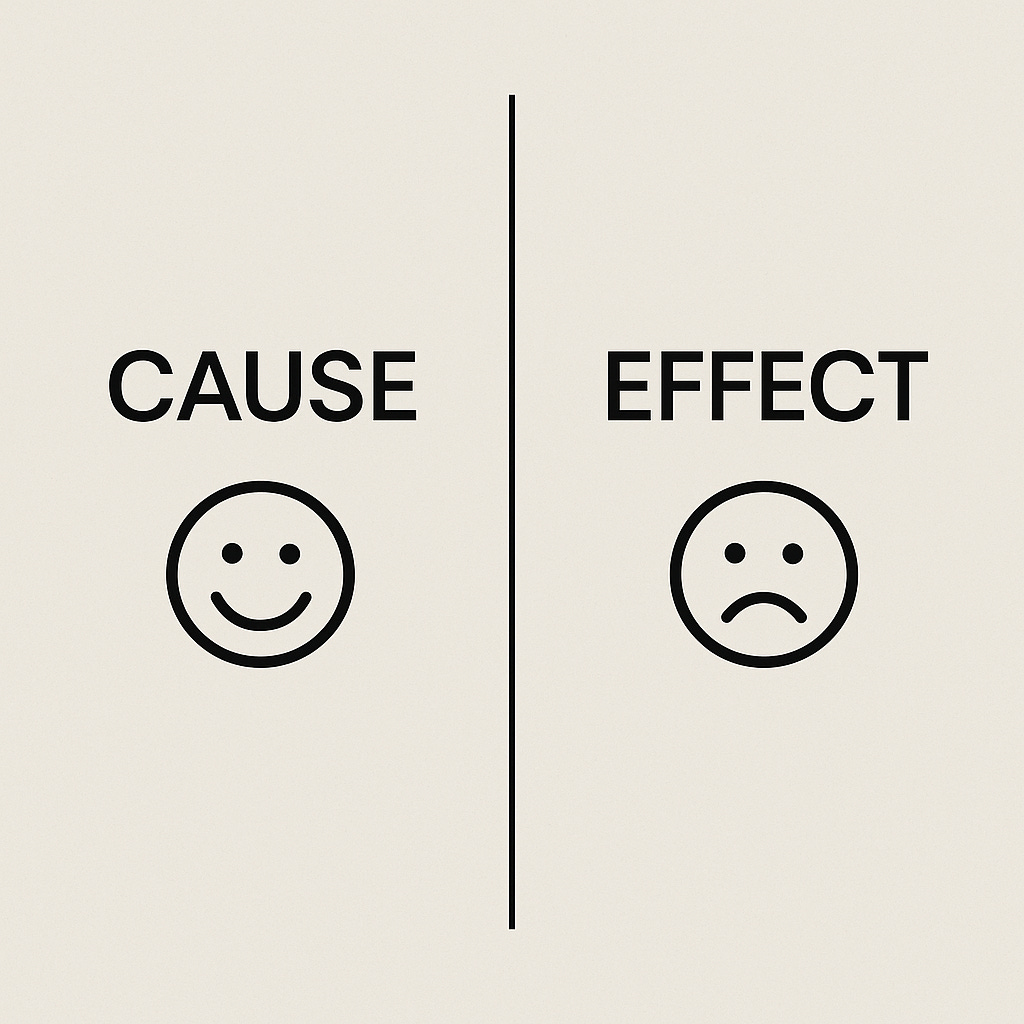

This is usually when I present the framework of Cause/effect, which I’ve talked about previously.

The idea is that at any given moment, you’re choosing to position yourself on one side of the line. In one of them, you’re a victim of whatever consequences and effects the world imposes on you. It doesn’t matter if you enjoy them or not; after all, you don’t have any control over them. The decision to think about yourself this way removes your privilege to complain about whatever’s happening in your life, after all, you’re framing yourself as a victim of the consequences.1 The alternative is ownership and seeing yourself as the cause of something, revealing a higher degree of agency.

Once students grasp the concept, he first step is to have them reflect on past situations and assess which side of the model they believe they were on. It’s easier for them to recognize when they were the Cause of good things. Not so much when it comes to that which limits them. Slowly, however, they get to a point where they’re able to admit that a bad grade was actually their fault and not the teacher’s, or that a project didn’t work because they didn’t do their part, not because their colleagues were bad teammates. This first step starts a cascading effect that must be rewarded with praise. They are making an effort to see how they can take ownership, and a word of encouragement can go a long way here.

Afterwards, we set up a signal, a verbal or physical code that allows me to point out in a funny, quick way whenever they’re framing themselves as victims of the effects of other people’s decisions.

The final step in developing this skill is to create an Ownership Journal, where they record situations from their past, present, or future in which they either took ownership or want to.

Emotional Intelligence

I ask you to pause and remember your teen years. Were they easy? I don’t think so. Everything is happening, everywhere, all at the same time. You’re dealing with so many questions, changes, disappointments, experiments…To expect extreme emotional control by someone who’s facing these many different things is ludicrous.

The first thing we must do as mentors is to give them space to feel.2 Now, giving them space to feel is not the same thing as validating everything they’re feeling.

A lot of the time, educators tend to fall heavily into one side of the spectrum: validating everything the students are going through or showing that their perspective is “wrong” and they should feel a different way. Both balance and timing are key elements in helping a student at a deeper level.

My personal approach starts with increasing awareness of what they feel and what’s causing it, allowing them to have both the space and language that they need to do so.

One of the first suggestions I make to my mentees is to have them add the expression “right now” to whatever emotion they’re feeling. Teens tend to oversimplify their emotional framework, assuming that what they feel in the moment will last forever. Not only that, but they’ll also connect whatever emotion they’re feeling with their sense of identity. It’s important to help them make the distinction between a fleeting feeling and their sense of self.

“I’m so dumb!” becomes “I’m super frustrated with myself right now!”, which eventually gets to “I guess I gave my best, and that has to matter for something, right?”. In the beginning, you must be the one helping them reframe these kinds of expressions until they can do it by themselves. By applying this, you’re increasing the capacity of using language to control their emotional landscape and the physical sensations that result from that.

This newfound skill of awareness and articulation of their emotions allows you both to brainstorm positive triggers that they can bring to their day-to-day, increasing the buffer between action and reaction, ultimately helping them get to a point where they choose how to respond to something, including their own feelings.

I like to help students prepare for those moments where they’re feeling emotionally overwhelmed by setting up a series of positive triggers that they can use. Good moments are great to prepare for bad moments.

If they enjoy music, why not have a playlist of songs that make them feel balanced?3 Or make a Pinterest board with pictures that symbolize a version that they would like to embody? The MVA, when they’re feeling down, is to listen to the playlist or look at the board - low resistance, high chance of increasing positive momentum.

Even though these look like small things, they can help interrupt a pattern of negative emotion and at least give them a chance to try and change their emotional landscape.

A final reminder: you’re a mentor, not a therapist. Know the difference and act accordingly.

Self-Confidence

If you talk enough with high schoolers, you’ll realize that a lot of them tend to be in this oscillating state of low confidence and high ego, going from “I’m worth nothing” to “I can do anything that I want!” in about 5 seconds. They’re both extremely impotent against the world and extremely secure in themselves. They’re also oblivious to this dynamic and what it represents: a defense mechanism. If you’re listening intently, you’ll quickly see through that and uncover a part of their self-image and the level of confidence they hold.

The way I approach students who may have lower self-confidence depends on how much rapport I’ve built with them (which is a valid principle for everything that I do with a mentee). My biggest concern is figuring out how acknowledging their lack of confidence will affect their goals and relationships. I may point that out directly or work on it indirectly and then, through hindsight, make them recognize what changed.

Let me walk you through my formula for helping students build Confidence.

In my research and experience, I’ve found that self-confidence is mostly unlocked by movement, not thought. If you could think your way through it, we would have many more people with higher levels of Confidence.

People who enjoy thinking often understand that reality is fluid, denying you a final answer. Seeking the truth is hard when applied to yourself. You can always have different questions and perspectives that will poke holes in whatever theories you have. If your mind roams free, you won’t arrive at a sequence of thoughts that allows you a conclusion. Unless you bring action into the mix.

Don’t get me wrong. I love thinking! It’s a great way to unlock new growing opportunities. Action, however, balances that, bringing a sense of reality to something that’s sometimes purely abstract.

Action is harder than thought. As educators, we know this. So do students. That’s why they can recognize, either on their own or with your guidance, the inner resistance that often stops them from taking action. Sometimes, it’s laziness; other times, fear. Regardless of it, there’s an inner conflict happening. To be able to push past it and act is the first step in developing a greater sense of self-confidence. Students become someone who does things, even when they’re scared, lazy, or anxious.

Once students start doing things, we must help them develop resilience. No matter what they do, no matter how much they plan, challenges will arise. It’s a “fundamental property of reality” that they’ll find challenges, sooner or later.

There are two ideas that I try to instill in students, hopefully before they’re facing the challenges. The first one is that it doesn’t speak to their personal ability. The second one is that they should see it as a reason to change paths, not stop altogether.

Because challenges are a “fundamental property of reality”, they don’t speak to your capacity levels; they’re just part of everyone’s process. Sure, you can use your ownership to realize how you can improve and overcome that challenge, but you use your emotional intelligence to understand that who you are is not what needs improvement, but what you do or how you act.

I use video games often to prove this point.

In role-playing games, when a certain area is inaccessible, you don’t assume that you can’t get there. You just know that you still don’t have what’s necessary to enter it. It’s part of the natural progression of the game. Students, when realizing this, will also understand that a challenge is, indeed, a detour to unlock certain skills, not a reason to stop playing.

So, by now, students are acting and have developed this resilience that comes from seeing challenges as detours, not endings. The final piece comes from experience.

Students must develop, through action and resilience, a portfolio of experiences that they can point to in moments of doubt about themselves. This “trophy case” will be used to prove to them that they can trust themselves, after all, they’ve gone through many different experiments, acting and adapting as they go.

Suddenly, self-confidence is no longer a word floating in the ether, but an emotional state rooted in true, concrete examples of situations and actions they’ve overcome.

No matter what’s happening, they can always point to what they went through as a way to argue for their own true self-confidence (as opposed to ego, which portrays confidence with no evidence). No matter what’s happening, they can always say that, even though they were scared, they didn’t stop. Even though they’ve faced challenges, they kept improving and moving.

This is why it’s fundamental for students to write down and memorize these kinds of situations, using them as the foundational argument around their own confidence.

By combining action, resilience, and experience, you unlock a student’s Self-Confidence.

Task and Knowledge Management

Of the many flaws that the education system has, a lack of a subject that teaches students how to process notes and manage their tasks is the one that’s been bothering me the most lately. Even in alternative education, a lot of times, we lack a framework for students to be able to organize their projects, tasks, and notes. This is probably why, of all these skills, students feel more drawn to this one at the beginning of our mentorship process.

When it comes to knowledge management, I introduce my mentees to “Building a Second Brain” by Tiago Forte. We read excerpts of the book and watch a couple of videos together to understand the basic structure, but then, my main focus is on task management.

A lot of students call it “time management”, which is an illusion (something I learned from my father, who taught a course on the subject).

Time is a constant; you have no control over it. What you can do is to control your attention and how or to what you allocate it. Managing your own attention fosters the idea of ownership much strongly than managing time.

The first step to these skills is to help them pick their Second Brain. Maybe it’s a digital one, through Notion, Notes, Google Docs, or Tana (my personal favourite). I try to be on top of the different software, as a way to help students unlock their full potential, but most of the students end up choosing a Google Doc or Notion. Some of them, however, prefer a physical notebook, and that’s fine as well.

In all systems of task and knowledge management, the first step is to capture. You’re collecting all of the different tasks and notes into a single place and then filtering them based on what you want/need. This will be the student’s inventory and starting point.

I encourage students to write down all kinds of things in there, from fun activities they want to do (such as trying a new video game, which educators can also enjoy), to school assignments (paper due next week), to events happening in their lives (like a family dinner on Saturday). Once they get into the habit of writing everything in a single place, then we get to explore how to filter them.

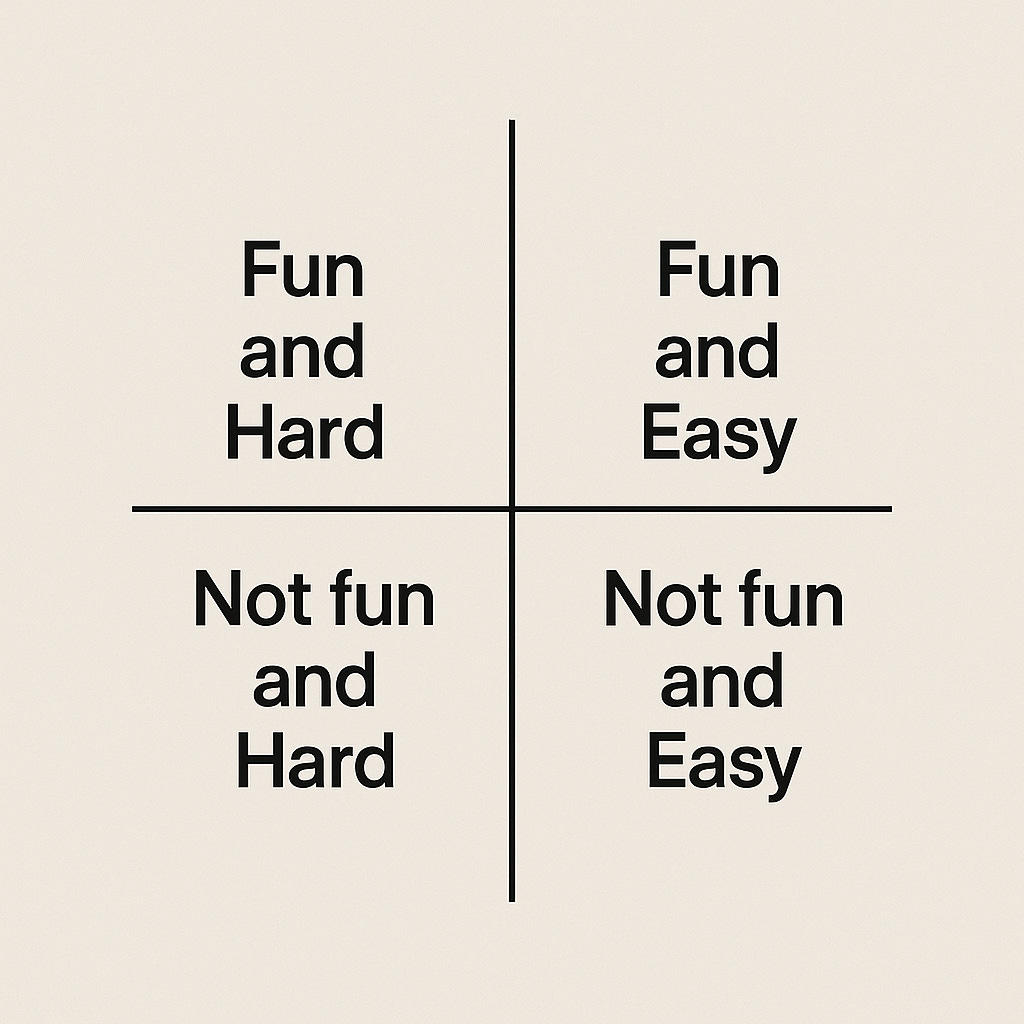

I usually lead with something I call the Fun/Challenge matrix.

This matrix, as the name suggests, signals how fun and challenging something is. Hopefully, all tasks fall into one of the four quadrants:

Fun and Hard;

Fun and Easy;

Not fun and Hard;

Not fun and Easy.

Here’s what this looks like with real examples from a mentee I met last week:

Fun and Hard -> Reading a complex text on a topic they’re enjoying;

Fun and Easy -> Practice Rock songs on the drums;

Not fun and Hard -> Doing 1 hour of Math;

Not fun and Easy -> Organizing your journal.

I’m aware that most productivity theories will encourage you to “eat the frog”, and do what’s not fun and hard at first, before moving to everything else. Even though I see value in that method, I don’t think it’s universal. Some of my mentees enjoy building momentum by having “easy wins” before jumping into the hard stuff, and I think that’s fair. My rule is that students get to organize their tasks in any way they prefer, as long as they’re doing what needs to be done.

How do we figure that out? I like using the “321 Method”, a very easy framework to organize tasks once they’re catalogued: 3 tasks, 2 minutes, 1 focus period.

Out of all the things they have, students pick 3 tasks that have a higher priority. Usually, we aim for 2 hard tasks, fun and not fun, and 1 easy task. Those are their daily goals and need to get done no matter what.

Every day, they’re spending 2 minutes clarifying the 3 goals for the next day.

Finally, during that same day, there’s always at least 1 period of focused time to work on these goals.

It’s a pretty easy-to-use framework. Students really enjoy it, and my favorite part is that it allows them to build momentum and have concrete proof of work, which, as we’ve seen, builds self-confidence.

Other than specific tasks, a lot of times, students want to develop habits, which is where we go back to the concept of MVAs. All of my mentees have Minimum Viable Actions, something so easy that they can guarantee that they’ll do it no matter what. It can be as small as they want, as long as they bring “the perfect streak”.

Teenagers, much like adults, implement new habits by setting up overly ambitious goals, transposing their current level of self-discipline and interest. I’m all up for ambition, but you either have this extreme passion and go berserk, or the best alternative is to use MVAs.

Here’s an example of a conversation with a student, clarifying their MVA.

Student: I was thinking I could set up a goal to do 1 hour of Math every day.

Me: You haven’t been doing any Math for the last 2 weeks, do you think that goal is Sustainable?

S:You’re right, I’ll do the 30 minutes.

M: Well, that’s good. Let’s say that we want to set up a goal that has a 100% chance of being achieved. You need to have complete ownership of the task, making sure it gets done every single day until our next session. No matter how little, how much time do you think you could guarantee doing?

S: That would be like 5 minutes.

M: Perfect.

5 minutes don’t look like a lot, but most of the time, students end up doing more than that anyway. The main focus is to remove the pressure and resistance of a new thing, making it easier to engage with it. Even if you forgot about doing math all day and are about to go to sleep, you can force yourself to do 5 minutes of math instead of a 30-minute session. After students build a perfect streak of, say, 2 weeks, we change the MVA based on that and increase the dosage.

They’re not only sustainably building the habit, but they’re also able to consistently act, which allows them to work on their self-confidence. That’s why MVAs matter so much to me.

Networking

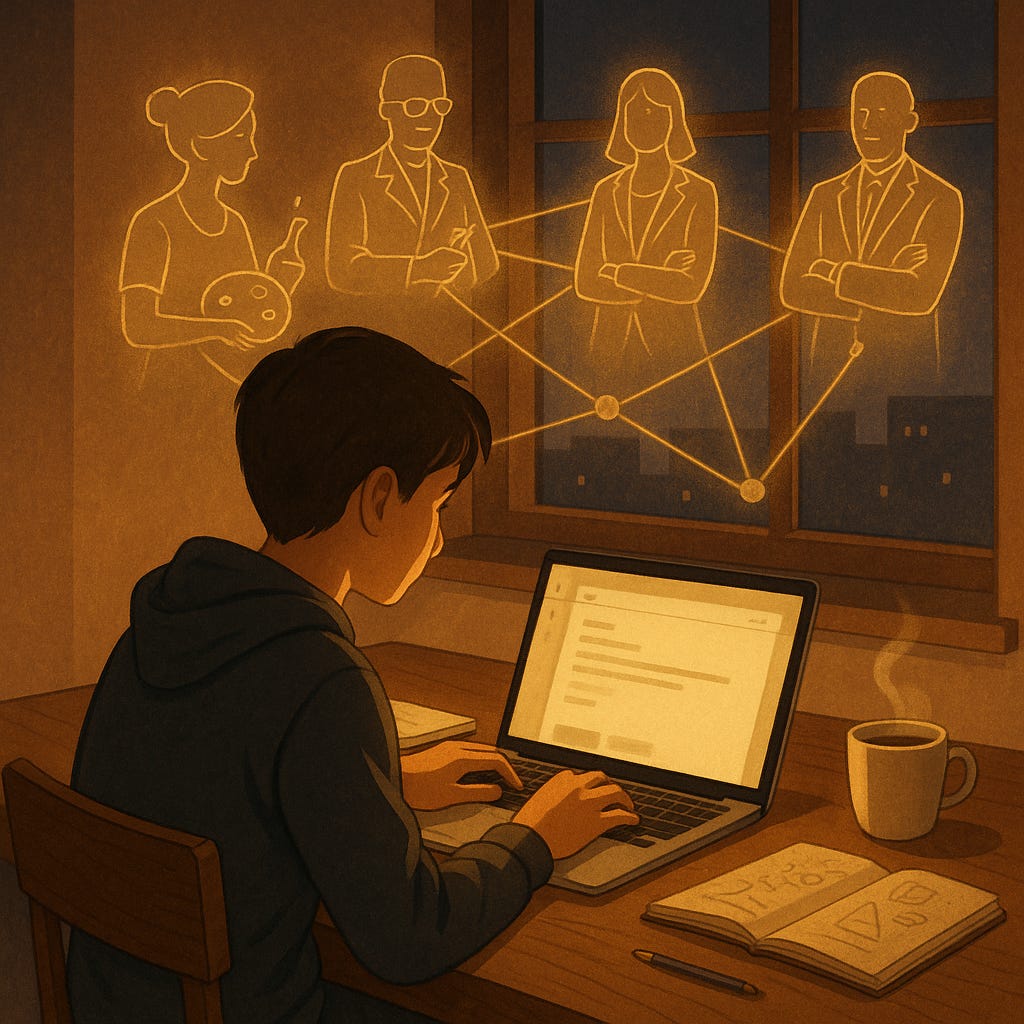

The last skill that I usually work on with my mentees is Networking.

Once again, my music experience plays a huge role in the way that I think about this, especially as a mentor. When studying jazz guitar and wanting to understand rhythm, my teacher would encourage me to talk with drummers since they could explain it far better than he could. I apply this same principle with my mentees today.

There’s a high chance that I don’t know every single technical skill that students may need to develop their projects. I’ve had a student work in Procedural Math and 3D shaders for the past 3 years, and I have a hard time even defining those. How can I mentor him in that area? I just can’t! But I can encourage him to reach out to people who are part of that space and ask for help. This has happened with students with multiple different interests, and my default is always to help them figure out who can help them in a better way.

Mastery demands proximity to masters.

There are two approaches that I teach: cold reach-outs and content creation.

Cold reach-outs to people they admire are one of the best habits students can have. LinkedIn, Social Media, or plain email are all good venues for connection and taking a moment to craft a message, and then dealing with the outcomes of that helps them build their sense of agency and resilience (important for Ownership and Self-Confidence).

Even though it’s rather easy to convince a student to do this, the hardest part is to help them navigate the emotional discomfort of following up. Students think that by sending a follow-up email, they’re being rude, pushy, obnoxious, or impertinent.

If someone doesn’t reply, they automatically assume that it is worthless to reach out again. People who live in the real world know that, most times, that’s not the case. Sometimes, they’re busy, sure, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t or are unwilling to help.

That’s why follow-ups are the backbone of networking. Gentle reminders, coming from a place of true admiration and desire to connect.

Cold emailing (and follow-ups) gets easier by applying the second strategy: content creation.

If you have a portfolio to show (through a Website, a social media account, a Substack, a YouTube channel,…), you get to use those different pieces of content to connect more effectively. Not only do they demonstrate passion and credibility (after all, you’re going through the work of building it), but they also allow you to portray yourself as someone worth talking with.

Reaching out to their favorite graphic designer through email with three different music posters makes it easier for them to see how serious a student is and to understand how they can help compared with a plain email with no context.

By sending an email where, in a few key sentences, students include hyperlinks to articles they wrote that showcase their ideas, they give others a clearer sense of their worldview and thinking.

The main goal is to increase the chances of a student being remembered by whomever they’re trying to connect with, providing a natural reason to follow up by sending additional material from their portfolio.

Content creation facilitates connection, and networking at a young age allows students to unlock new opportunities in life.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this overview of my approach to mentorship. I’m considering creating a community where students can develop these skills through monthly calls and shared resources. If you’re a student interested in joining or a parent who knows someone who might benefit from this, feel free to reach out at joao@comtexto.pt.

Finally, if you have any questions about what I’ve shared, I’m always happy to continue the conversation!

Now, of course, this has a lot of nuance; it highly depends on the student and the actual story. A lot of them will point out things that are just inherent properties of their lives, and no matter how you look at it, are not, at all, a choice. However, most students point out things that are not part of this category.

Which is why, in the Ownership session, we always start by validating their feelings before moving on the a different framework.

I prefer using the term “balanced” instead of “joyful” or “happy.” The goal of MVAs is to reduce friction as much as possible. If students perceive them as attempts to invalidate their emotions, they’ll be less likely to engage, much like telling someone in the middle of an anxiety attack to “just relax.” We all know how ineffective that is.